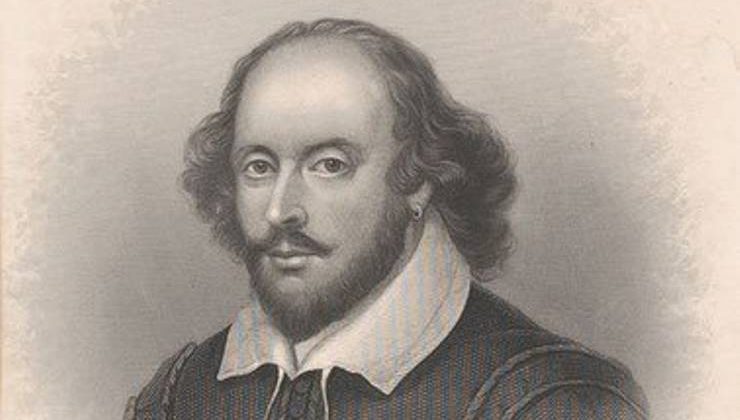

Shakespeare’s Life

SHAKESPEARE’S ANCESTRY

As a brief introductory detail it should be mentioned that, during the sixteenth century, there were many families with the name Shakespeare in and around Stratford. “Shakespeare” appears countless times in town minutes and court records, spelled in a variety of ways, from Shagspere to Chacsper. Unfortunately, there are very few records that reveal William Shakespeare’s relationship to or with the many other Stratford Shakespeares. Genealogists claim to have discovered one man related to Shakespeare who was hanged in Gloucestershire for theft in 1248, and Shakespeare’s father, in an application for a coat of arms, claimed that his grandfather was a hero in the War of the Roses and was granted land in Warwickshire in 1485 by Henry VII. No historical evidence has been discovered to corroborate this story of the man who would be William Shakespeare’s great-grandfather, but, luckily, we do have information regarding his paternal and maternal grandfathers. The Bard’s paternal grandfather was Richard Shakespeare (d. 1561), a farmer in Snitterfield, a village four miles northeast of Stratford.

There is no record of Richard Shakespeare before 1529, but details about his life after this reveal that he was a tenant farmer, who, on occasion, would be fined for grazing too many cattle on the common grounds and for not attending manor court. There is no record of Richard Shakespeare’s wife, but together they had two sons (possibly more), John and Henry. Richard Shakespeare worked on several different sections of land during his lifetime, including the land owned by the wealthy Robert Arden of Wilmecote, Shakespeare’s maternal grandfather. Robert Arden (d. 1556) was the son of Thomas Arden of Wilmecote, Shakespeare’s maternal great-grandfather, who probably belonged to the aristocratic family of the Ardens of Park Hall. He was catholic and married more than once (we know the name of his second wife — Agnes Hill) and he fathered no fewer than eight daughters. He became the stepfather of Agnes’ four children. Robert Arden had accumulated much property, and when he died, he named his daughter (Shakespeare’s mother) Mary, only sixteen at the time, one of his executors. He left Mary some money and, in his own words, “all my land in Willmecote cawlide Asbyes and the crop apone the grounde, sowne and tyllide as hitt is”.

SHAKESPEARE’S PARENTS

Shakespeare’s father, John, came to Stratford from Snitterfield before 1532 as an apprentice glover and tanner of leathers. John Shakespeare prospered and began to deal in farm products and wool. It is recorded that he bought a house in 1552 (the date that he first appears in the town records), and bought more property in 1556. Because John Shakespeare owned one house on Greenhill Street and two houses on Henley Street, the exact ******** of William’s birth cannot be known for certain. Sometime between 1556 and 1558 John Shakespeare married Mary Arden, the daughter of the wealthy Robert Arden of Wilmecote and owner of the sixty-acre farm called Asbies. The wedding would have most likely taken place in Mary Arden’s parish church at Aston Cantlow, the burial place of Robert Arden, and, although there is no evidence of strong piety on either side of the family, it would have been a Catholic service, since Queen Mary I was the reigning monarch. We assume neither John nor Mary could write — John used a pair of glovers’ compasses as his signature while Mary used a running horse — but it did not prevent them from becoming important members of the community. John Shakespeare was elected to a multitude of civic positions, including ale-taster of the borough (Stratford had a long-reaching reputation for its brewing) in 1557, chamberlain of the borough in 1561, alderman in 1565, (a position which came with free education for his children at the Stratford Grammar School), high bailiff, or mayor, in 1568, and chief alderman in 1571.

Due to his important civic duties, he rightfully sought the title of gentleman and applied for his coat-of-arms in 1570 (see picture on left). However, for unspecific reasons the application was abruptly withdrawn, and within the next few years, for reasons just as mystifying, John Shakespeare would go from wealthy business owner and dedicated civil servant to debtor and absentee council member. By 1578 he was behind in his taxes and stopped paying the statutory aldermanic sub¤¤¤¤¤¤ion for poor relief. In 1579, he had to mortgage Mary Shakespeare’s estate, Asbies, to pay his creditors. In 1580 he was fined 40 pounds for missing a court date and in 1586 the town removed him from the board of aldermen due to lack of attendance. By 1590, John Shakespeare owned only his house on Henley Street and, in 1592 he was fined for not attending church. However, near the very end of John Shakespeare’s life, it seems that his social and economic standing was again beginning to flourish. He once again applied to the College of Heralds for a coat-of-arms in 1596, and, due likely to the success of William in London, this time his wish was granted. On October 20 of that year, by permission of the Garter King of Arms (the Queen’s aid in such matters) “the said John Shakespeare, Gentlemen, and…his children, issue and posterity” were lawfully entitled to display the gold coat-of-arms, with a black banner bearing a silver spear (a visual representation of the family name “Shakespeare”). The coat-of-arms could then be displayed on their door and all their personal items. The motto was “Non sanz droict” or “not without right. The reason cited for granting the coat-of-arms was John Shakespeare’s grandfather’s faithful service to Henry VII, but no specifics were given as to what service he actually performed. The coat-of-arms appears on Shakespeare’s tomb in Stratford. In 1599 John Shakespeare was reinstated on the town council, but died a short time later, in 1601. He was probably near seventy years old and he had been married for forty-four years. Mary Shakespeare died in 1608 and was buried on September 9.

SHAKESPEARE’S BIRTH

The baptismal register of the Holy Trinity parish church, in Stratford, shows the following entry for April 26, 1564: Gulielmus filius Johannes Shakespeare. The actual date of Shakespeare’s birth is not known, but, traditionally, April 23, St George’s Day, has been Shakespeare’s accepted birthday, and a house on Henley Street in Stratford, owned by William’s father, John, is accepted as Shakespeare’s birth place. However, the reality is that no one really knows when the great dramatist was born. According to the Book of Common Prayer, it was required that a child be baptized on the nearest Sunday or holy day following the birth, unless the parents had a legitimate excuse. As Dennis Kay proposes in his book Shakespeare

If Shakespeare was indeed born on Sunday, April 23, the next feast day would have been St. Mark’s Day on Tuesday the twenty-fifth. There might well have been some cause, both reasonable and great — or perhaps, as has been suggested, St. Mark’s Day was still held to be unlucky, as it had been before the Reformation, when altars and crucifixes used to be draped in black cloth, and when some claimed to see in the churchyard the spirits of those doomed to die in that year. . . .but that does not help to explain the christening on the twenty-sixth.(54)

No doubt Shakespeare’s true birthday will remain a mystery forever. But the assumption that the Bard was born on the same day of the month that he died lends an exciting esoteric highlight to the otherwise mundane details of Shakespeare’s life.

SHAKESPEARE’S SIBLINGS

William Shakespeare was indeed lucky to survive to adulthood in sixteenth-century England. Waves of the plague swept across the countryside, and pestilence ravaged Stratford during the hot summer months. Mary and John Shakespeare became parents for the first time in September of 1558, when their daughter Joan was born. Nothing is known of Joan Shakespeare except for the fact that she was baptized in Stratford on September 15, and succumbed to the plague shortly after. Their second child, Margaret, was born in 1562 and was baptized on December 2. She died one year later. The Shakespeares’ fourth child, Gilbert, was baptized on October 13, 1566, at Holy Trinity. It is likely that John Shakespeare named his second son after his friend and neighbor on Henley Street, Gilbert Bradley, a glover and the burgess of Stratford for a time. Records show that Gilbert Shakespeare survived the plague and reached adulthood, becoming a haberdasher, working in London as of 1597, and spending much of his time back in Stratford. In 1609 he appeared in Stratford court in connection with a lawsuit, but we know no details regarding the matter. Gilbert Shakespeare seems to have had a long and successful career as a tradesman, and he died a bachelor in Stratford on February 3, 1612. In 1569, John and Mary Shakespeare gave birth to another girl, and named her after her first born sister, Joan. Joan Shakespeare accomplished the wondrous feat of living to be seventy-seven years old — outliving William and all her other siblings by decades. Joan married William Hart the hatter and had four children but two of them died in childhood. Her son William Hart (1600-1639) followed in his famous uncle’s footsteps and became an actor, performing with the King’s Men in the mid-1630s.

His most noted role was that of Falstaff. William Hart never married, but the leading actor of the restoration period, Charles Hart, is believed to have been William Hart’s illegitimate son and grandnephew to Shakespeare. Due to the fact that Shakespeare’s children and his other siblings did not carry on the line past the seventeenth century, the descendants of Joan Shakespeare Hart possess the only genetic link to the great playwright. Joan Shakespeare lost her husband William a week before she lost her brother William in 1616, and she lived the rest of her life in Shakespeare’s birthplace. Joan died in 1646, but her descendants stayed in Stratford until 1806. Undoubtedly already euphoric that Joan had survived the precarious first few years of childhood, the Shakespeares’ joy was heightened with the birth of their fourth daughter, Anne, in 1571, when William was seven years old. Unfortunately, tragedy befell the family yet again when Anne died at the age of eight. The sorrow felt by the Shakespeares’ over the loss of Anne was profound, and even though they were burdened by numerous debts at the time of her death, they arranged an unusually elaborate funeral for their cherished daughter. Anne Shakespeare was buried on April 4, 1579. In 1574, Mary and John Shakespeare had another boy and they named him Richard, probably after his paternal grandfather. Richard was baptized on March 11 of that year, and nothing else is known about him, except for the fact that he died, unmarried, and was buried on February 4, 1613 — a year and a day after the death of Gilbert Shakespeare. Mary gave birth to one more child in 1580. They christened him on May 3 and named him Edmund, probably in honor of his uncle Edmund Lambert. Edmund was eager to follow William into the acting profession, and when he was old enough he joined William in London to embark on a career as a “player”. Edmund did not make a great reputation for himself as an actor, but, in all fairness, cruel fate, and not his poor acting abilities, was likely the reason. Edmund died in 1607 — not yet thirty years old. He was buried in St. Saviour’s Church, in Southwark, on December 31 of that year. His funeral was costly and magnificent, with tolling bells heard across the Thames. It is most likely that William planned the funeral for his younger brother because William would have been the only Shakespeare wealthy enough to afford such an expensive tribute to Edmund. In addition, records show that the funeral was held in the morning, and as Dennis Kay points out, funerals were usually held in the afternoon. It is probable that the morning funeral was arranged so that Shakespeare’s fellow actors could attend the burial of Edmund.

SHAKESPEARE’S EDUCATION AND CHILDHOOD

Shakespeare probably began his education at the age of six or seven at the Stratford grammar school, which is still standing only a short distance from his house on Henley Street and is in the care of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Although we have no record of Shakespeare attending the school, due to the official position held by John Shakespeare it seems likely that he would have decided to educate young William at the school which was under the care of Stratford’s governing body. The Stratford grammar school had been built some two hundred years before Shakespeare was born and in that time the lessons taught there were, of course, dictated primarily by the beliefs of the reigning monarch. In 1553, due to a charter by King Edward VI, the school became known as the King’s New School of Stratford-upon-Avon. During the years that Shakespeare attended the school, at least one and possibly three headmasters stepped down because of their devotion to the catholic religion proscribed by Queen Elizabeth. One of these masters was Simon Hunt (b. 1551), who, in 1578, according to tradition, left Stratford to pursue his more spiritual goal of becoming a Jesuit, and relocated to the seminary at Rheims. Hunt had found his true vocation: when he died in Rome seven years later he had risen to the position of Grand Penitentiary. Like all of England’s great future poets and dramatists, Shakespeare learned his reading and writing skills from an ABC, or horn-book. Robert Speaight in his book, Shakespeare: The Man and His Achievement, describes this book as a primer framed in wood and covered with a thin plate of transparent horn. It included the alphabet in small letters and in capitals, with combinations of the five vowels with b, c, and d, and the Lord’s Prayer in English.

The first of these alphabets, which ended with the abbreviation for ‘and’, began with the mark of the cross. Hence the alphabet was known as ‘Christ cross row’ — the cross-row of Richard III, I, i, 55. A short catechism was often included in the ABC book (the ‘absey book’ of King John, I, i, 196). (10)

In The Merry Wives of Windsor, there is a comical scene in which the Welsh headmaster tests his pupil’s knowledge, who is appropriately named William. There is little doubt that Shakespeare was recalling his own experiences during his early school years. As was the case in all Elizabethan grammar schools, Latin was the primary language of learning. Although Shakespeare likely had some lessons in English, Latin composition and the study of Latin authors like Seneca, Cicero, Ovid, Virgil, and Horace would have been the focus of his literary training. One can see that Shakespeare absorbed much that was taught in his grammar school, for he had an impressive familiarity with the stories by Latin authors, as is evident when examining his plays and their sources. Even though scholars, basing their argument on a story told more than a century after the fact, accept that Shakespeare was removed from school around age thirteen because of his father’s financial and social difficulties, there is no reason whatsoever to believe that he had not acquired a firm grasp of Latin and English at the school and that he had continued his studies despite his removal from the Stratford grammar school. The famous quote by Nicholas Rowe in 1709, in which he states that Shakespeare “acquir’d that little Latin he was Master of” and tells us that Shakespeare was prevented by his father’s poor fortune from “further proficiency in that Language” should be read with an extremely critical eye. As we all know, Shakespeare was a young man when he began to write magnificent plays that had plots based entirely on Latin stories, such as the Menaechmi of Plautus, and striking imagery that was drawn from the ¤¤¤¤morphoses of Ovid and the Lives of Plutarch.

There are other fragmented and dubious details about Shakespeare’s life growing up in Stratford. He is supposed to have worked for a butcher, in addition to helping run his father’s business. There is a fable that Shakespeare stole a deer from Sir Thomas Lucy at Charlecote, and instead of serving a prison sentence, fled from Stratford. Although this is surely a fictitious incident, there exist a few verses of a humorous ballad mocking Lucy that has been connected to Shakespeare. “Edmond Malone records a version of two verses of the Lucy Ballad collected by one of the few great English classical scholars, Joshua Barnes, at Stratford between 1687 and 1690. Barnes stopped overnight at an inn and heard an old woman singing it. He gave her a new gown for the two stanzas which were all she remembered”:

Sir Thomas was so covetous

To covet so much deer

When horns enough upon his head

Most plainly did appear

Had not his worship one deer left?

What then? He had a wife

Took pains enough to find him horns

Should last him during life. (Levi, 35)

Shakespeare’s daily activities after he left school and before he re-emerged as a professional actor in the late 1580s are impossible to trace. Suggestions that he might have worked as a schoolmaster or lawyer or glover with his father and brother, Gilbert, are all plausible. So too is the argument that Shakespeare studied intensely to become a master at his literary craft, and honed his acting skills while traveling and visiting playhouses outside of Stratford. But, it is from this period known as the “lost years”, that we obtain a vital piece of information about Shakespeare: he married a pregnant orphan named Anne Hathaway.

SHAKESPEARE’S MARRIAGE AND CHILDREN

Recordings in the Episcopal register at Worcester on the dates of November 27 and 28, 1582, reveal that Shakespeare desired to marry a young girl named Anne. There are two different documents regarding this matter, and their contents have raised a debate over just whom Shakespeare first intended to wed. Were there two Annes? Was Shakespeare in love with one but in lust with the other? Was Shakespeare ready to join in matrimony with the Anne of his dreams only to have an attack of conscience and marry the Anne with whom he had carnal relations? To discuss the controversy properly we should look at the documents in question. The first entry in the register is the following record of the issue of a marriage license to one Wm Shakespeare:

Anno Domini 1582…Novembris…27 die eiusdem mensis. Item eodem die supradicto emanavit Licentia inter Wm Shaxpere et Annam Whateley de Temple Grafton.1

The next entry in the episcopal register records the marriage bond granted to one Wm Shakespeare:

Noverint universi per praesentes nos Fulconem Sandells de Stratford in comitatu Warwici agricolam et Johannem Rychardson ibidem agricolam, teneri et firmiter obligari Ricardo Cosin generoso et Roberto Warmstry notario publico in quadraginta libris bonae et legalis monetae Angliae solvend. eisdem Ricardoet Roberto haered. execut. et assignat. suis ad quam quidem solucionem bene et fideliter faciend. obligamus nos et utrumque nostrum per se pro toto et in solid. haered. executor. et administrator. nostros firmiter per praesentes sigillis nostris sigillat. Dat. 28 die Novem. Anno regni dominae nostrae Eliz. Dei gratia Angliae Franc. et Hiberniae Reginae fidei defensor &c.25.2 The condition of this obligation is such that if hereafter there shall not appear any lawful let or impediment by reason of any precontract, consanguinity, affinity or by any other lawful means whatsoever, but that William Shagspere on the one party and Anne Hathwey of Stratford in the diocese of Worcester, maiden, may lawfully solemnize matrimony together, and in the same afterwards remain and continue like man and wife according unto the laws in that behalf provided…

Three possible conclusions can be reached from the above records: 1) The Anne Whateley in the first record and the Anne Hathwey in the second record are the same woman. Some scholars believe that the name Whateley was substituted accidentally for Hathwey into the register by the careless clerk. “The clerk was a nincompoop: he wrote Baker for Barber in his register, and Darby for Bradeley, and Edgock for Elcock, and Anne Whateley for Anne Hathaway. A lot of ingenious ink has been spilt over this error, but it is surely a simple one: the name Whateley occurs in a tithe appeal by a vicar on the same page of the register; the clerk could not follow his own notes, or he was distracted” (Levi, 37). Moreover, some believe that the couple selected Temple Grafton as the place for the wedding for reasons of privacy and that is why it is recorded in the register instead of Stratford. 2) The Wm Shaxpere and the Annam Whateley who wished to marry in Temple Grafton were two different people entirely from the Wm Shagspere and Anne Hathwey who were married in Stratford. This argument relies on the assumption that there was a relative of Shakespeare’s living in Temple Grafton, or a man unrelated but sharing Shakespeare’s name (which would be extremely unlikely), and that there is no trace of this relative after the issue of his marriage license. 3) The woman Shakespeare loved and the woman Shakespeare finally married were two different Annes. Not many critics support this hypothesis, but those that do use it to portray Shakespeare as a young man torn between the love he felt for Anne Whateley and the obligation he felt toward Anne Hathwey and the child she was carrying, which was surely his. In Shakespeare, Anthony Burgess constructs a vivid scenario to this effect:

It is reasonable to believe that Will wished to marry a girl named Anne Whateley. The name is common enough in the Midlands and is even attached to a four-star hotel in Horse Fair, Banbury. Her father may have been a friend of John Shakespeare’s, he may have sold kidskin cheap, there are various reasons why the Shakespeares and the Whateleys, or their nubile children, might become friendly. Sent on skin-buying errands to Temple Grafton, Will could have fallen for a comely daughter, sweet as May and shy as a fawn. He was eighteen and highly susceptible. Knowing something about girls, he would know that this was the real thing. Something, perhaps, quite different from what he felt about Mistress Hathaway of Shottery. But why, attempting to marry Anne Whateley, had he put himself in the position of having to marry the other Anne? I suggest that, to use the crude but convenient properties of the old women’s-magazine morality-stories, he was exercised by love for the one and lust for the other. I find it convenient to imagine that he knew Anne Hathaway carnally, for the first time, in the spring of 1582… (57)

Whichever argument one chooses to accept, it is fact that Shakespeare, a minor at the time, married Anne Hathaway, who was twenty-six and already several months pregnant. Anne was the eldest daughter, and one of the seven children of Richard Hathaway, a twice-married farmer in Shottery. When Richard died in 1581, he requested his son, Bartholomew, move into the house we now know as Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, and maintain the property for his mother, Richard’s second wife and Anne’s stepmother. Anne lived in the cottage with Bartholomew, her step-mother, and her other siblings. No doubt she was bombarded with a barrage of household tasks to fill her days at Hewland Farm, as it was then called. After her marriage to Shakespeare, Anne left Hewland Farm to live in John Shakespeare’s house on Henley Street, as was the custom of the day. Preparations for the new bride were made, and for reasons unknown, her arrival greatly bothered John Shakespeare’s current tenant in the house, William Burbage. A heated fight ensued, and John refused to release Burbage from his lease, so Burbage decided to take the matter to a London court. On July 24, 1582, lawyers representing both sides met and reached an agreement – John would release Burbage from his lease.

The Shakespeares’ first child was Susanna, christened on May 26th, 1583, and twins arrived in January, 1585. They were baptized on February 2 of that year and named after two very close friends of William — the baker Hamnet Sadler and his wife, Judith. The Sadlers became the godparents of the twins and, in 1598, they, in turn, named their own son William. Not much information is known about the life of Anne and her children after this date, except for the tragic fact that Hamnet Shakespeare died of an unknown cause on August 11, 1596, at the age of eleven. By this time Shakespeare had long since moved to London to realize his dreams on the English stage — a time in the Bard’s life that will be covered in depth later on — and we do not know if he was present at Hamnet’s funeral in Stratford. We can only imagine how deeply the loss of his only son touched the sensitive poet, but his sorrow is undeniably reflected in his later work, and, particularly, in a passage from King John, written between 1595 and 1597:

Young Arthur is my son, and he is lost:

I am not mad: I would to heaven I were!

For then, ’tis like I should forget myself:

O, if I could, what grief should I forget!

Preach some philosophy to make me mad,

And thou shalt be canonized, cardinal;

For being not mad but sensible of grief,

My reasonable part produces reason

How I may be deliver’d of these woes,

And teaches me to kill or hang myself:

If I were mad, I should forget my son,

Or madly think a babe of clouts were he:

I am not mad; too well, too well I feel

The different plague of each calamity….

I tore them from their bonds and cried aloud

‘O that these hands could so redeem my son,

As they have given these hairs their liberty!’

But now I envy at their liberty,

And will again commit them to their bonds,

Because my poor child is a prisoner.

And, father cardinal, I have heard you say

That we shall see and know our friends in heaven:

If that be true, I shall see my boy again;

For since the birth of Cain, the first male child,

To him that did but yesterday suspire,

There was not such a gracious creature born.

But now will canker-sorrow eat my bud

And chase the native beauty from his cheek

And he will look as hollow as a ghost,

As dim and meagre as an ague’s fit,

And so he’ll die; and, rising so again,

When I shall meet him in the court of heaven

I shall not know him: therefore never, never

Must I behold my pretty Arthur more. (III.iv.45-91)

SHAKESPEARE AS ACTOR AND PLAYWRIGHT

We know very little about Shakespeare’s life during two major spans of time, commonly referred to as the “lost years”. The lost years fall into two periods: 1578-82 and 1585-92. The first period covers the time after Shakespeare left grammar school until his marriage to Anne Hathaway in November of 1582. The second period covers the seven years of Shakespeare’s life in which he must have been perfecting his dramatic skills and collecting sources for the plots of his plays. “What could such a genius accomplish in this direction during six or eight years? The histories alone must have required unending hours of labor to gather facts for the plots and counter-plots of these stories. When we think of the time he must have spent in reading about the pre-Tudor dynasties, we are at a loss to estimate what a day’s work meant to him. Perhaps he was one of those singular geniuses who absorbs books. George Douglas Brown, when discussing Shakespeare, often used to say he knew how to ‘pluck the guts’ out of a tome” (Neilson 45). No one knows for certain how Shakespeare first started his career in the theatre, although several London players would visit Stratford regularly, and so, sometime between 1585 and 1592, it is probable that young Shakespeare could have been recruited by the Leicester’s or Queen’s men. Whether an acting troupe recruited Shakespeare in his hometown or he was forced on his own to travel to London to begin his career, he was nevertheless an established actor in the great city by the end of 1592. In this year came the first reference to Shakespeare in the world of the theatre. The dramatist Robert Greene declared in his death-bed autobiography that “There is an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers heart wrapt in a Players hide supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you; and, being an absolute Johannes Factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country.” After Green’s death, his editor, Henry Chettle, publicly apologized to Shakespeare in the Preface to his Kind-Heart’s Dream:

No related posts.

Bu yazı yorumlara kapatılmıştır.